Among the abstract expressionists, Robert Motherwell remains one of the hardest to define. Was he a collagist, painter, printer, or scholar? Robert Motherwell: A Survey, on view now at Jerald Melberg Gallery, proves he was all of these.

Daniel Haxall, a visiting abstract expressionist scholar from Kutztown University, says the exhibit at the Sharon Amity Road gallery “offers a timely chance to assess his career overall” as we approach the centennial of the artist’s birth.

The show contains work from 1951 to 1990, a year before the artist died. It is a bright, lyrical circus with the idea of tension connecting the pieces in one fluid thread. Motherwell explores the struggle of man versus himself; our emotions against our attempt to control them.

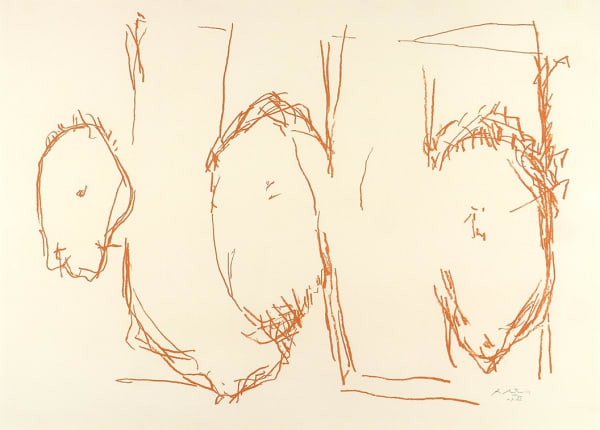

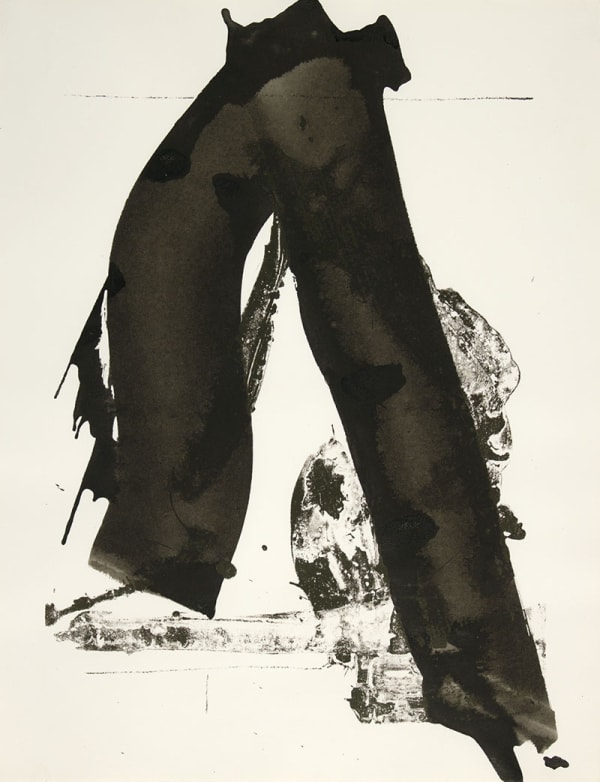

Tension takes many forms, as the visitor will see in the juxtaposed ovoid and rectilinear shapes of the Elegies to the Spanish Republic. While the title clearly points to the Spanish Civil War, the first sketch was drawn to accompany an unrelated 1948 Harold Rosenberg poem, confirming Motherwell sought to portray a universal struggle. Jerald Melberg Gallery holds an example from 1990 in which the standard forms are composed of rust-colored swipes and outlined with a veil of thin, blue paint.

A group of works from the Open series hang in the same room. The word points to Motherwell’s attitude. He welcomed chance, the unplanned, and all possibilities of life. In Open No. 89, ochre paint partially obscures a red base and dark straight lines, though others emerge to form sides of open squares. By avoiding a total erasure of the original painting, the artist insists the viewer see his process, showing us that the act of reworking the composition is part of the art.

Robert Motherwell was born in Aberdeen, Washington in 1915, showing an interest in art at an early age. He studied philosophy at Stanford, Harvard, and Columbia universities.

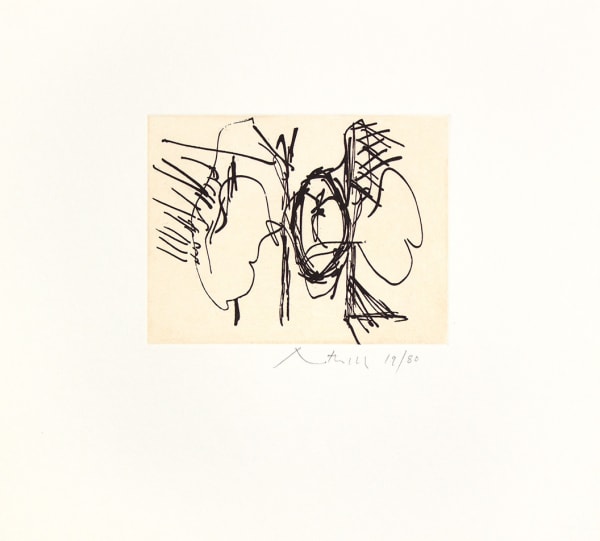

He helped establish the abstract expressionist group in 1940s New York, a movement anchored in the process of creation. The word they used was automatism, defined by the Museum of Modern Art as “registering subconscious impulses.” The viewer only sees the remains of these impulses: stripes of slung paint, tight scratches of ink, and ripped and arranged paper. According to Haxall, Motherwell’s modus operandi was “generally to not represent a thing, but the effect the thing produces.”

Motherwell began a lifelong love of collage in 1943 with a request for a group show from Peggy Guggenheim. Using fine handmade papers and editions of his own prints, he could rip and rearrange to his heart’s desire. In McCartney in Brazil, Motherwell places sheet music beneath a blown up version of a Brazilian cigarette packet and next to a painted black triangle, whose natural red coloring shows along its edges.

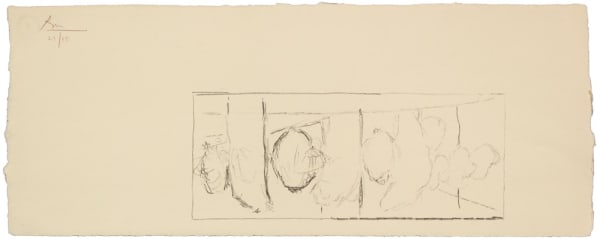

The last room of the gallery is filled with prints, a favorite medium of the artist because of the ability to rework the same themes through series. The eight pieces of the May Linen Suite feel scraggly and bare compared to the previous rooms’ sonorant compositions. The forms in each are stripped echoes of Motherwell’s go-to themes, like the hollow men (#5), inspired by a T.S. Eliot poem, and the Elegies (#3). Nearby, the brown and black Primal Signs (I-IV) seek inspiration in non-western sources uncorrupted by material life.

Motherwell avoided materialism by always opting for abstract representations of feelings and emotions. His compositional choices may seem foreign to the untrained eye, but this show suggests there is much more to be learned from and said about Robert Motherwell.